How Big a Tree Should I Plant?

Article #3 in the Series “So, You Want to Plant a Tree!”

Peter Duinker, Halifax Tree Project

2023-05-10

A tree starts out as a seed and grows through every possible size until it dies. Sometimes trees die young (most trees in Nove Scotian woodlands’ natural regeneration die as seedlings or saplings). When we seek a tree to plant in the urban environment, we want the new tree to live – a long time. What difference does size of tree at time of planting make? Let’s delve into this interesting question.

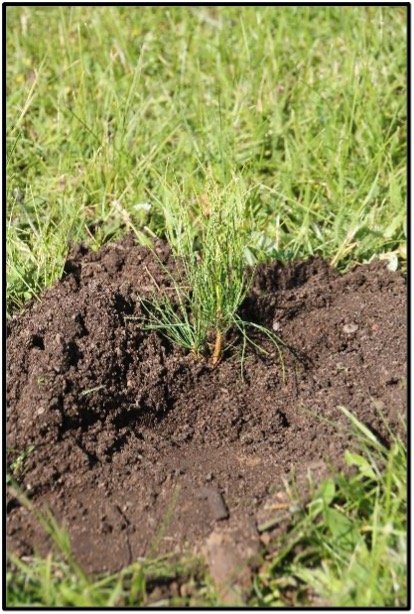

You could plant a seed, and that would surely cost nothing, or at least next to nothing, but most people are inclined to want to plant a tree. At the small end, you could plant a 10- or 15-cm tall seedling (see the photo of a white-pine seedling). This is the size of tree – mostly conifer – that gets planted in the woods in reforestation projects. At the other extreme are so-called caliper trees. These are usually 60 mm diameter at the root collar, and usually they are delivered to the planting site in balled-and-burlapped format (see the photo). Between these two extremes are potted trees in a range of sizes often sold by reference to the soil quantity in the pot (see the photo).

First, let’s think about price. Let’s assume you are buying the tree(s) you want to plant. It seems obvious that the larger the tree purchased, the more expensive. Species differences aside, you could probably buy a seedling for a few dollars, and a balled-and-burlapped tree for several hundred dollars, and potted trees somewhere between. In the last couple of decades, I have purchased potted trees for anywhere from $50 to $200. Lately, as one would expect, they are more expensive. The price differences by size reflect the amount of time and effort it takes in the nursery to grow a tree for sale to plant.

So, besides price, on what basis might you favour small vs large, or the other way around? Partly it depends on what the garden centre or nursery has for sale. They might have sugar maples only in 2-gallon pots and red oaks only in 5-gallon pots. The sugar maples would be cheaper but you might really want a red oak. But let’s say, for this discussion, that you could choose an oak seedling 40 cm tall in a small pot, or an oak in a 1-gallon, 2-gallon, 5-gallon, 7-gallon, or 10-gallon pot? The biggest here might be 3 m tall and 40 mm diameter at the root collar.

Three issues are at play here from my perspective. One issue is your tolerance for the time it takes for a small tree to grow large. I have planted seedlings on my postage-stamp urban property and waited for 5-10 years for them to grow to the 10-gallon-pot size. If this is an issue for you, you might want to start with a larger tree. The second issue is tree protection. In general, the smaller the tree you plant, the more protection it will need for a longer time – you don’t want a deer or beaver or some other tree-eating varmint to munch your tree in one bite! One errant soccer ball or youngster’s inadvertent tromp can end the life of a seedling but probably not a sapling.

The third issue is, for me, the most important. It relates to the rooting behaviour of the purchased tree. There are two parts to this issue. One is whether the root-to-shoot masses are balanced at the time of planting. Whether potted or balled-and-burlapped, there are generally fewer roots than the crown shoots need for rapid initial growth, so the newly planted tree has to spend energy to establish a proper root-to-shoot balance. This means that most of the new tree’s development is allocated to roots, not the crown. The larger the tree at the time of planting, the more serious this issue can be. It’s why newly planted street trees, almost always balled-and-burlapped stock, seem to languish for several years before exhibiting much crown growth. When they are dug up in the nursery fields, probably 80-90% of their roots are left behind. The tree needs to address that imbalance before really showing vigour in crown development.

However, potted trees also have issues. If the potted trees are not replanted into larger pots each year, the roots can easily begin encircling the root mass as they hit the walls of the pot and can go nowhere but around and around the pot wall. When this is the case, the tree should not be planted out unless the encircling root mass is cut in a special way to stop the roots from continuing this encircling behaviour once out-planted. Generally speaking, the smaller the tree at the time of planting, the less of an issue encircling roots will be.

If you have a glance at the article on this site entitled “At Home with Trees” (https://www.halifaxtreeproject.com/at-home-with-trees), you will see that my six special trees include two I purchased (sugar maple and red oak, both potted and about 3 m tall at the time of planting) and four I got free as seedlings (white pine, yellow birch, eastern hemlock, and European beech). Apart from the hemlock, which was suppressed for a long time by a scruffy tree overhead, the purchased trees have not grown better than the seedlings. So I come away from my experience with the conclusion that if cost is an issue for a property owner, plant small, be patient, and water and protect the seedlings. Moreover, adore the little tree just like you might a kitten or puppy – small can be incredibly beautiful!