Why Did That Tree Die? Was It Vandalism?

Peter Duinker, Halifax Tree Project

2022-05-16

There is precious little research on the role of vandalism in causing trees to die. Clearly, the role of vandalism might be expected to be greatest when trees are small, especially those just planted in high-risk locations such as the streetside ecosystem (Richardson and Shackleton, 2014). Here are my observations of the role of vandalism on street trees in Halifax. Since we have no scientifically defensible data, I must rely on what I have seen.

First off, let’s define vandalism as willful damage to trees. This does not include damage to trees caused by sloppy vegetation management around new trees – by this I mean damage to young trees by uncareful operators of mowers and trimmers. Vandalism is rare in trees beyond their juvenile stages of development. Sure, we see initials carved in smooth-bark trees like beech, but that’s about it. It’s the young trees we are concerned about.

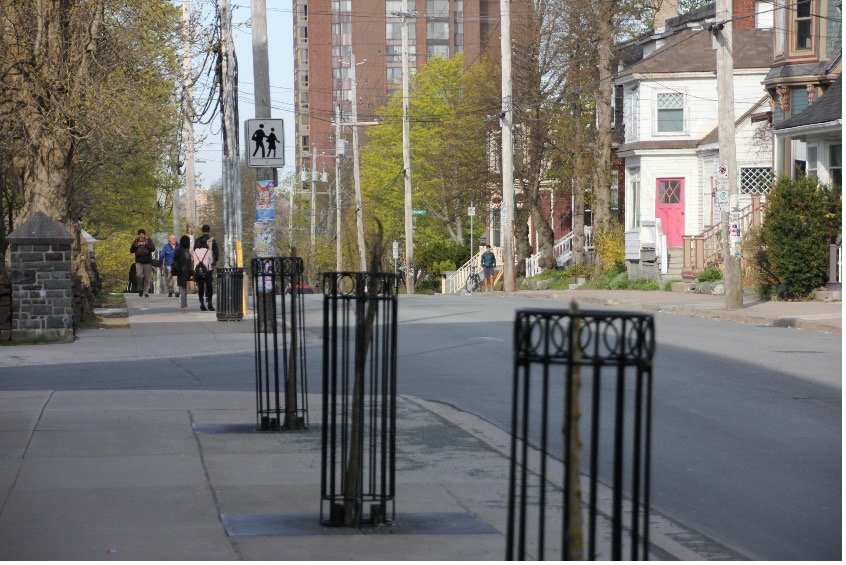

Photo 1: Act of vandalism on Dalhousie Campus, Halifax. (Photo by: Peter Duinker)

In my opinion, of all the drivers of young-tree mortality in Halifax, vandalism is a minor factor. Like most observers, I have seen my share of vandalized trees. Vivid in my memory is a group of trees on Coburg Road in front of Dalhousie’s Mona Campbell Building. The trees were installed in a hardscape with ground-level grates and a wrought-iron tree cage about 40 cm in diameter. One night, all four trees were broken off. They were broken precisely at the top of the 140-cm cages (see Photo 1), which clearly means that, in the street, vandals simply grabbed the trunks above the cages and ripped them sideways until they broke. One could be tempted to imagine that university students, on the way back to residence from a bender downtown, simply could not resist the temptation to rip those young trees down (Black (1978) corroborates this hypothesis).

Other instances of vandalism in my observations are rare. Recently, I wanted a Catalpa stump on Charles Street (the mature tree had been severely damaged by Hurricane Dorion in autumn 2019 and was removed the next year) to be left in the ground because several stump sprouts had emerged. Late in the growing season last summer (2021), I removed all suckers but three vital ones. They stood solid until about January this year when one went down (unknown cause), and then the other two were broken off in March 2022. It is clear that this was a case of vandalism. In hindsight, it would have been prudent to put caution tape on some stakes around the stump to warn off would-be vandals.

Photo 2: Girdled tree in Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo by: Peter Duinker)

My final example comes from Copenhagen where, during an urban-forest field trip, the group visited a skate park where some skaters must have been irritated beyond rationality by the litter dropping from the huge horse chestnut tree at the perimeter of the skating surface. They girdled the tree only weeks before we visited (see Photo 2). A disgusting act of vandalism.

What to do about tree vandalism? Black (1978) offered some approaches: special tree protective devices, careful species and location choices, and trying to instill a sense of community pride in the new trees in the neighbourhood. Thankfully, in Halifax our rates of tree mortality due to vandalism seem rather low. We’ll be reporting soon on that plus a range of other mortality factors in a paper analyzing the 5-year mortality rates of all the street trees we planted in Halifax during 2013-2016.

References

Black, M.E. 1978. Tree vandalism: some solutions. Journal of Arboriculture 4(5):114-116.

Richardson, E. and C. Shackleton. 2014. The extent and perceptions of vandalism as a cause of street tree damage in small towns in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 13:425-432.